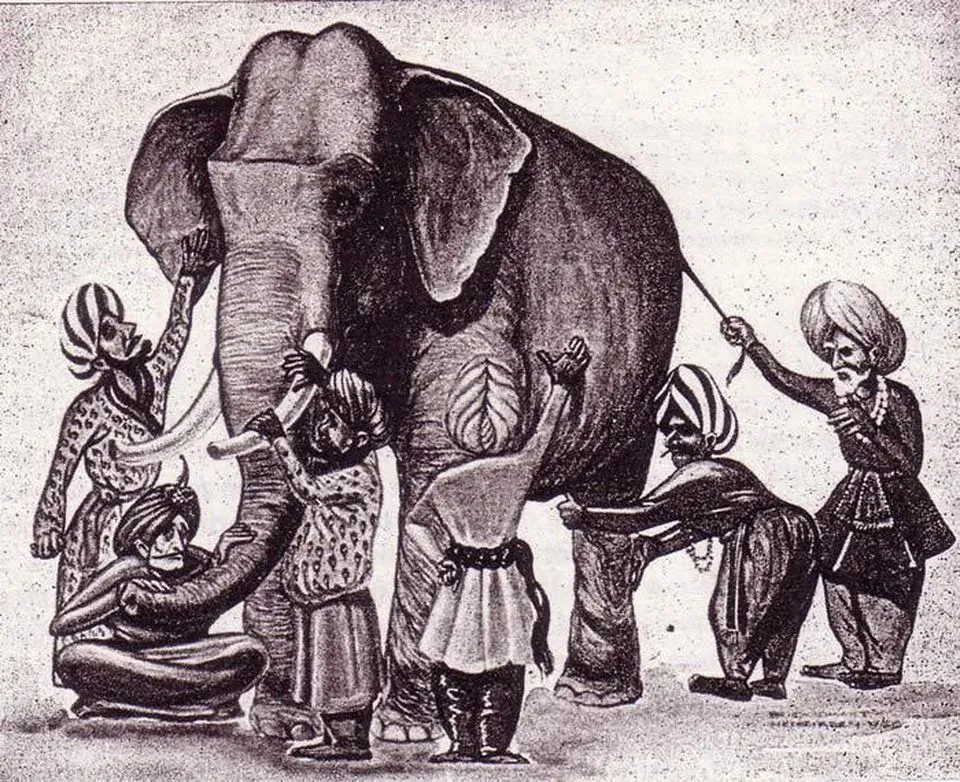

The blind men and the elephant

What an ancient story about the limits to our perception teaches us about our fragmented modern experience.

Elephants are so difficult to describe that there's something known as "the elephant test" in legal theory. The test is by the expression, "I know it when I see it," and it's invoked (by judges) whenever dealing with an especially difficult to describe concept.

With their unique characteristics and enormous size, elephants defy definition. Ask six people to explain what an elephant looks like, and you'll get six similar but different answers. Ask those same six people to agree on their definition, and you might be in for a fight.

That's one lesson from a parable that's over a thousand years old — that of the blind men and the elephant. And though the story is ancient, it's more applicable today than ever.

Because today, technology makes it possible for anyone to hold an elephant in their hand — and everyone is blind.

Before we get to that, let's refresh on the story.

The parable

Over a thousand years old, the parable of the blind men and the elephant is believed to have originated in India.

The story goes like this:

A group of blind men heard that a strange animal, called an elephant, had been brought to the town, but none of them were aware of its shape and form.

Out of curiosity, they said: “We must inspect and know it by touch, of which we are capable.” So they sought it out, and when they found it they grabbled about it.

The first person, whose hand landed on the trunk, said, “This being is like a thick snake.” For another one, whose hand reached its ear, it seemed like a kind of fan. As for another person, whose hand was upon its leg, said, "The elephant is a pillar like a tree-trunk." The blind man who placed his hand upon its side said the elephant, "is a wall." Another who felt its tail, described it as a rope. The last felt its tusk, stating the elephant is that which is hard, smooth, and like a spear.

As the men share their observations, they discover them to be inconsistent and conflicting. Confused, they accuse each other of deception and become violent.

In one variation of the story, a sighted man arrives in time to describe the entire elephant to the blind men, reconciling each man's account to the overall quality of the elephant. Each man learns how their individual knowledge was correct though incomplete. They are enlightened. This version of the parable has a happy ending.

Five lessons from the six blind men

The parable of the blind men and the elephant has many lessons. Here are five:

1. Perception is not reality

What you are capable of perceiving limits what you can possibly perceive. For example, certain wavelengths of light fall outside of the range that our eyes can see. This is also true for the other senses. There is more information "out there" than we can observe, and we are oblivious to that additional information.

In addition, attention reduces perception. When we focus our attention, we reduce reality to a manageable set of information. What we attend to — and therefore what we perceive — is only ever a glimpse of reality.

There's still yet another limitation.

Concepts used to make sense of observations filter our perception — e.g. applying the concept of a snake to make sense of the elephant's nose becomes a frame through which the blind man tries to make sense of the elephant. The blind man understands the novel concept by relating it to the known concept.

This creates another problem.

2. Concepts are not reality

Concepts not only limit perception, the limits spill over into communication.

Communication is the exchange of information. Return to the example of "the elephant is like a snake." By making an analogy to the shared concept of a snake, the observer believes they are communicating clearly. However, the listener has no way of knowing how the communicator's observations fit the shared concept. Without knowing what an elephant's nose is like, the listener could conclude that the elephant has a forked tongue, sharp fangs, or is covered in smooth scales.

When it comes to communication, the perception of a concept by the listener becomes their reality.

3. So perception is reality?

What people perceive isn't reality, but no one seems to care: People believe what they perceive.

Put the other way around: What you perceive, you believe.

Which is why you (and everyone else) are skeptical of the observations of others by default. This skepticism can degrade into all kinds of problems — because no one wants to be wrong.

4. No one wants to be wrong

Violence is a poor way to settle debates — one that's been used for millennia and is unlikely to disappear from mankind anytime soon. In one version of the blind men and the elephant, confusion leads to violence.

No one wants to be wrong. To better understand why, examine "being wrong" through the SCARF model:

- People run from threats to Status, and being wrong — especially in front of others — is a serious threat.

- People run from threats to Certainty. Being wrong re-introduces uncertainty.

- People run from threats to Autonomy. Giving up your belief and taking on another's threatens one's sense of power and control.

- People run from threats to Relatedness. Fighting over beliefs pits people against each other, suspending trust and blocking relationship.

For the blind men, not wanting to be wrong ends in violence.

In a group setting, disagreements are contagious through mimesis and can escalate into aggressive behaviors. You can even imagine a darker end to the blind men and the elephant. Consider this alternative way to conclude the story:

... On hearing the observations of the sighted man, the blind men become enraged. They refuse to accept the sighted man's claims. They are suspicious over whether the outsider can even see. They convince each other that the sighted man is a liar who is trying to take advantage of the group. United in their fear and anger, the blind men attack and slaughter the sighted man.

This ending draws on ideas from René Girard's mimetic theory (a subject for another day).

5. When you generalize, you make mistakes

It's so tempting to jump to conclusions, but inductive reasoning depends upon rich observations — and we already saw how perception is busted.

Making generalizations based on limited (and error-prone) observations is a good way to bake problems into your beliefs.

What's terrifying is how often we do generalize based on limited information — something we do all the time by relying on stories to make sense.

(For more on how we use stories to make sense, see Daniel Kahneman and "What you see is all there is" (WYSIATI).)

How to learn from the blind men

"Stop, drop, and roll" became a slogan in the 1950s when flammable clothing became dangerously popular. Always useful to remember in case you spontaneously combust, it's time to adapt the expression for cognitive dissonance: Stop, probe, and ponder.

When confronted with conflicting information, resist the urge to react by doubling down on what you know. Instead, stop, probe, and ponder. Remember: No one wants to be wrong. If you think everyone else wrong, you're probably wrong too.

Ask questions. Make more observations. Reason abductively: Imagine as many possible explanations as you can for the set of observations, remaining open to even more. Imagine the observations are right but the understanding is wrong.

Ask, "How is this right?"

Whatever new observations you make, share them with people less familiar with the subject under scrutiny, and learn what they think. Then keep going.

To know why you believe what you believe without being dogmatic is a superpower.

So about those elephants we carry around

Today, we experience more and more of reality through a thin piece of technology, one that everyone carries around all day long. These devices constrain our perceptions in every way, from senses to attention to concepts.

Like the blind men, we are oblivious to these constraints. We falsely believe that everyone has a similar experience to our own — after all, everyone has a phone. And though our phones are different, we have access to the same information.

But we deal with elephants.

Like the conflicting observations made by the blind men, each of us ends up with a different experience of reality, one mediated by the phone. Content is personalized to your interests. News is personalized to your views. You could even have the same two people using the same exact app and both still have an entirely different experience.

Unlike the blind men and the elephant, there will be no one coming to make sense of our differences, no one to patiently help us understand.

This is Babel.

Toward a shared reality

Yet there is hope, and it starts with awareness. We can accept the limitations on our perception and try to work around them. We can temper the need to conclude, to be certain. We can stay curious and ask questions. We must restrain our urge to resort to violence.

For each of us, whether at work or at home and through the stories we read or the stories we tell, we must do the hard work of building a shared reality.

That's the final lesson of the blind men and the elephant. So let's get to building, and maybe then our story will have a happy ending.

This is part of a growing collection of parables and stories used to understand people — in order to build better businesses, products, and services.