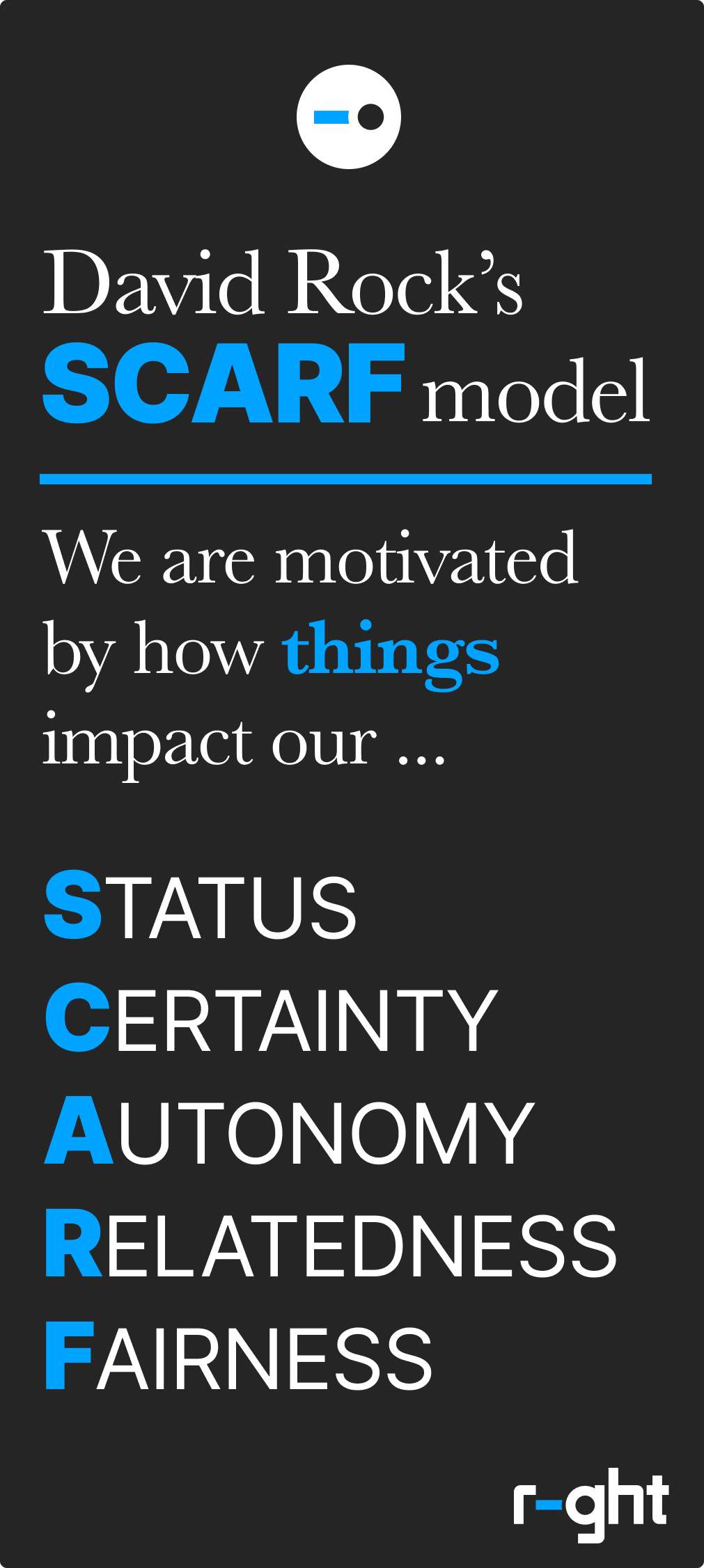

The SCARF model of motivation

The SCARF model by neuroscientist David Rock helps you troubleshoot — and even engineer — motivation, right into your product, service, or marketing.

You've done the research.

You know the job to be done.

You followed the path they take that fulfills desire.

You're confident your product, your service, your brand is what they want.

Yet there's a problem: Their apathy — your enemy — stands in the way of them giving your brand a shot.

How will you influence them to take a step in your direction? Thankfully, David Rock and his SCARF model provide a practical approach to answering this question.

Toss me the Rock SCARF

In 2008, David Rock, the founder of the NeuroLeadership Institute and author of the book Your Brain at Work, published his paper, SCARF: a brain-based model for collaborating with and influencing others [PDF]. Therein, Rock breaks down motivation into five domains:

Status

Certainty

Autonomy

Relatedness

Fairness.

S.C.A.R.F. 🧣

In this blog post, you'll learn how to apply the SCARF model, which is as easy as knowing a little about how the five domains influence behavior, and then asking how a person's perceptions motivate them to act given their particular set of circumstances.

Let's take a closer look.

Good vs. bad, approach vs. avoid, walk vs. run

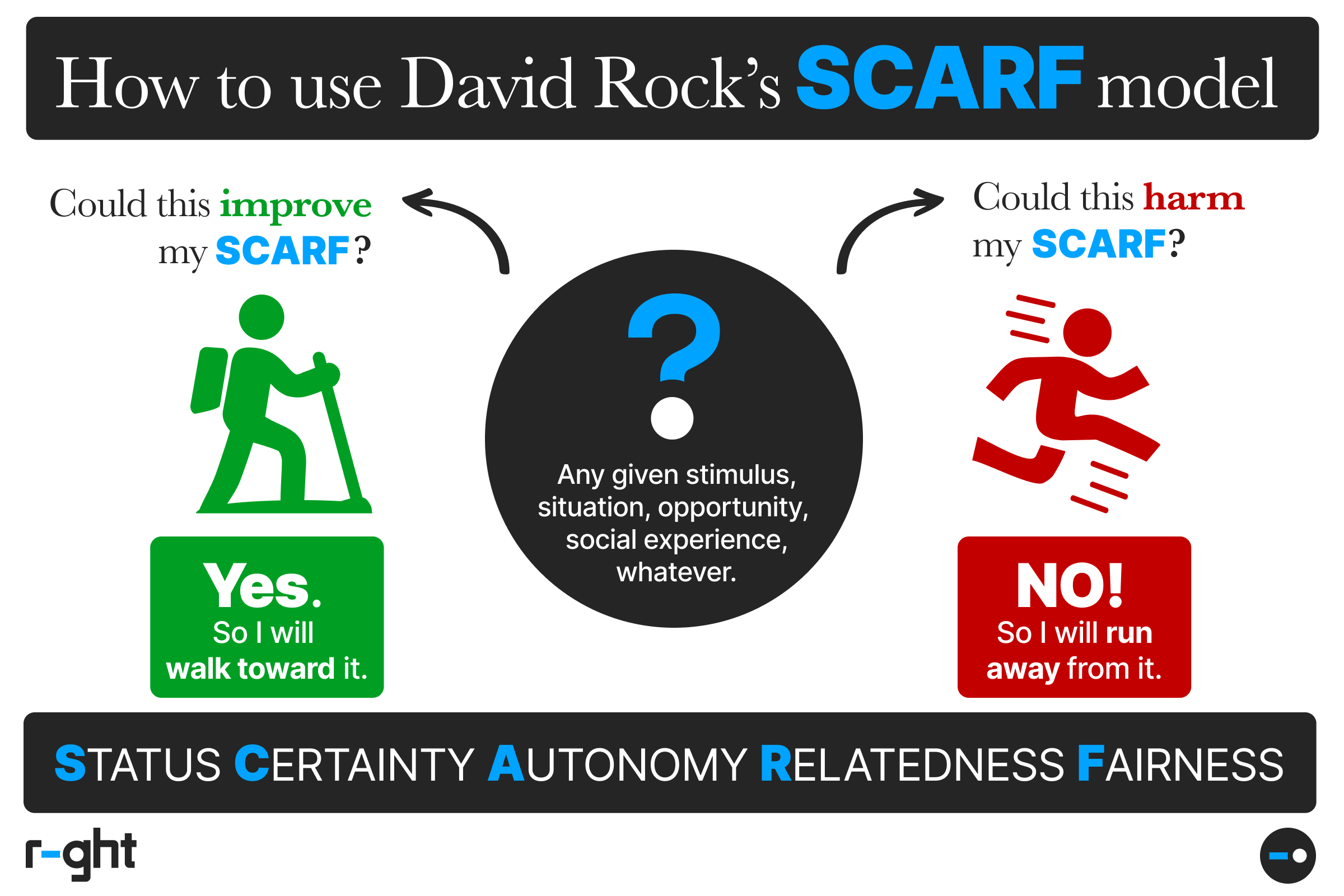

First, you need to understand a simple model — that of good vs. bad, approach vs. avoid, and walk vs. run.

You see, David Rock fuels the SCARF model by arguing that people categorize information, stimuli, experiences, whatever as either 'good' or 'bad.'

People classify information — a stimulus, a circumstance, an opportunity, a social experience, whatever — as either good or bad based on whether that thing is a reward or a threat, a benefit or a cost. We are motivated to approach anything good 🌱 and avoid anything bad 👹.

Rock says this organizing principle is a shortcut that our brains take to conserve energy, improving our odds of survival.¹ Good or bad things create an approach 🌱 versus avoid 👹 dynamic.

Rock tells us people walk toward rewards 🚶♂️ and run away from threats. 🏃♂️

Walk 🌱🚶♂️ versus run 🏃♂️👹

Armed with the good vs. bad, approach vs. avoid, walk vs. run way of organizing reality, you can now breakdown experiences across the five SCARF domains, asking for each domain whether a person would see an experience as good (walk toward 🌱🚶♂️) or bad (run away! 🏃♂️👹).²

How the SCARF model works

Now that you understand the fundamental way to assess a domain, commit to memory the five domains:

👑 Status

✅ Certainty

💪 Autonomy

🤝 Relatedness

⚖️ Fairness

Each domain can be assessed independently though don't get too hung up on the details.

Status 👑

Unlike the dwindling benefits you get as a Delta frequent flyer, status has an outsized impact on motivation. Status has to do with how an individual is perceived in relation to everyone else.

Rock's research found that improvements in status activate "primary reward circuitry" in the brain. Higher status individuals have lower stress and inflammation. They may even enjoy better health and live longer too.

No surprise, if a product, service, experience, or situation comes with improved status, people will feel motivated to take advantage.

On the other hand, Rock points out that the "perception of a potential or real reduction in status can generate a strong threat response." Rock's research found attacks on status can register on the brain in the same way as physical pain.

Perceived threats to status will prevent someone from taking chances. That could look like avoiding an opportunity where you know there's a chance of failure, being hesitant to stand out amidst your peers, or simply challenging, respectfully, a manager in a team meeting.

🌱🚶♂️ People walk toward things that improve their status.

🏃♂️👹 People run from things that threaten their status.

Certainty ✅

Certainty has to do with our ability to predict. If an individual has a good idea about how events should unfold, what to expect given a situation, they know what they need to know how to act.

Certainty runs hand-in-hand with confidence.

By contrast, when someone is uncertain of what to do given a situation, any action taken will, at best, cost them time and effort. At worst, action under uncertainy may leave them worse off.

Uncertainty leads to feeling blocked or stuck, to procrastination, to groping for information, or to "wait and see" for more information or to how others are acting.

🌱🚶♂️ People walk toward things that they understand clearly.

🏃♂️👹 People run from things they don't understand or find confusing.

Autonomy 💪

Autonomy is about power. The power to act is the power to wield control. This domain of SCARF is fundamental to motivation. Simply put: If an individual can't take action, they won't.

Inside company walls, autonomy is tricky business. As Rock points out, every individual gives up some autonomy when they work on a team. In large organizations, autonomy and bureaucracy butt heads.

Take, for example, a manager who sees an opportunity to shift budget to an opportunistic project. However, doing so would sidestep a known process and require bending unspoken, but clear, expectations about where the budget was to be spent. The manager's hands feel tied enough to simply not bother. The hassle of taking control is enough to keep the manager doing what's easy.

On the other hand, when you combine the freedom to act as you see fit with certainty about what to do, you don't have to think much at all. You just act.

🌱🚶♂️ People walk toward things if they have agency — the power to act.

🏃♂️👹 People run from things if they lack agency — the power to act.

Relatedness 🤝

Relatedness has special relevance to social experiences because it depends on feelings of connection to other people.

Consider what it's like when a person feels like they are on the same "side" as a someone else. Each person trusts that the other will act in their mutual best interest. Worry over risky behavior evaporates. Decisions get made without needing to know all the details.

Relatedness comes down to identifying with another person, seeing yourself in them (and vice versa). Even if you identify with someone you've never met, you're more likely to lend them a hand. After all, you feel like you're in their shoes, so helping them feels like helping yourself.

You might be familiar with the concept of relatedness from work by Robert Cialdini, writer of the bestselling book Influence. Cialdini sees relatedness as "liking," and names it one of the core principles of persuasion.

🌱🚶♂️ People walk toward people they identify with, with whom they relate.

🏃♂️👹 People run from people they see as unlike them.

Fairness ⚖️

Fairness is a bugaboo for everyone. Can you hear the refrain, "That's not fair!" People want the world to be fair — to get a "fair shake," to be treated in line with the Golden Rule.

(As any parent will tell you, children love pointing out unfairness.)

Rock says that, "Fair exchanges are intrinsically rewarding." So regardless of the reality, when it comes to day-to-day interactions, maintaining the perception of fairness is motivating — and any perceived unfairness or injustice will cause problems.

🌱🚶♂️ People walk toward situations they perceive as fair.

🏃♂️👹 People run from situations they perceive as unfair or injust.

Putting it all together

You might be building a product or designing a service. You might be the CEO of a Fortune 500 company. Perhaps you manage a small team. Maybe it's just you trying to understand your own behavior! No matter what, applying the SCARF model can help you.

And here are a few ways you can put it to work.

Using the SCARF model for better products and services

For product builders and service designers, use the SCARF model to engineer product and service features that motivate by design. For example:

- Features that benefit status (e.g. try gamification, launch certifications)

- Information that increases certainty (e.g. develop UX clarity through tooltips)

- Capabilities that improve autonomy (e.g. focus on making it easier to do their Job to Be Done)

- Integrations that establish connection and relatedness (e.g. make sharing and collaboration easy)

- Design that promotes fairness (e.g. accessibility)

More than anything, watch out for when your customers are not adopting your offering. Troubleshoot their motivation by examining the five domains and looking for problems.

When in doubt, start with certainty. Does the user know what will happen if they act? How can you help them remove that uncertainty?

How can you offer them status if they're a first mover? For example, building scarcity into a new product offering — as with marketing a waitlist — can make people want your product simply because they can't have it right away.

How can you make it easy to act? If a task should be easy to do, friction is not your friend. This is especially true of online transactions.

Using the SCARF model for better marketing

For marketers, always filter your messaging, stories, and brand campaigns through the SCARF model.

- Status. How will your target audience perceive the impact of your brand on their identity? Would they be proud to share your content, swag, or event with a peer or manager?

- Certainty. Is it clear the value you are offering? In a specific work, is what you want your audience to do clear? And is it clear what will happen if they take action?

- Autonomy. How easy is it for your target audience to take action? Are there any barriers to entry (e.g. cost, policies, paperwork), and if there are, how could you reduce friction at each step?

- Relatedness. Signal social proof. How do you show that your target audience is already adopting your product or service, signaling to a prospect that you understand their situation and that their peers are enjoying the benefits of your offering?

- Fairness. Will your target audience feel like they are being offered a fair price and a strong value? How can you increase the perception of value? How can you assuage concerns that your offering is in good faith, that your business acts as if "the customer is always right"?

As with products and services, debug situations that aren't playing out to expectations. Is there a lever to pull from the SCARF model?

Using the SCARF model to understand yourself

Let's talk about work. Projects are ripe for application of the SCARF model. Every project impacts status — how will it advance your standing to your boss or to your colleagues? If the project is prestigious, meaning it's difficult to do and has a desirable payoff space for the company, it strongly checks the status box.

But almost by nature, such a project is likely to come with a heaping dose of uncertainty.

It also is unlikely to be the kind of project you can do on your own — requiring the help or buy-in of others.

Relatedness and fairness can come into play too. For example, finding ways to get colleagues to care about the project — and then help you make progress on it — may require some salesmanship.

And if the project requires others to change, but those people see the work as unfair, well, you've got a big blocker to overcome.

In all of these cases, when you get blocked — and you will — use SCARF to debug motivation. Ask why you've hit a wall, why you're procrastinating, or why stakeholders aren't giving you the time of day.

When things are uncertain, ask for help. In fact, getting advice is a great way get the buy-in of others. Why? Because they necessarily have to put on your shoes and imagine themselves in your situation. In some cases, you can fix your uncertainty and relatedness problems by merely asking for help.

Put the SCARF model to work today, right now

David Rock originally created the SCARF model to help individuals understand their own motivations as well as the motivations of others in the workplace. What we find at R-ght is that the SCARF model is potent tool for figuring out motivations of all kinds.

To that end, you can put the SCARF model to work right now. Just apply it to something you're avoiding doing. What about it is making you run away? What would need to change for you to stop running, or even walk toward that thing?

Take the SCARF model and apply it to a product you've recently purchased. Run through the model, answering each question from your perspective before you bought the item.

Now you're getting the hang of it!

This is part of a growing collection of frames for understanding what's right for people — in order to build better businesses, products, and services.

Get further installments by subscribing to R-ght.

Footnotes

¹ In his 2008 paper, Rock elaborates on this 'good' and 'bad' organizing principle of the brain, connecting it to our instincts for survival:

According to integrative Neuroscientist Evian Gordon, the ‘minimize danger and maximize reward’ principle is an overarching, organizing principle of the brain (Gordon, 2000). This central organizing principle of the brain is analogous to a concept that has appeared in the literature for a long time: the approach-avoid response. This principle represents the likelihood that when a person encounters a stimulus their brain will either tag the stimulus as ‘good’ and engage in the stimulus (approach), or their brain will tag the stimulus as ‘bad’ and they will disengage from the stimulus (avoid). if a stimulus is associated with positive emotions or rewards, it will likely lead to an approach response; if it is associated with negative emotions or punishments, it will likely lead to an avoid response. The response is particularly strong when the stimulus is associated with survival. other concepts from the scientific literature are similar to approach and avoidance and are summarized in the chart below. [omitted]

The approach-avoid response is a survival mechanism designed to help people stay alive by quickly and easily remembering what is good and bad in the environment. The brain encodes one type of memory for food that tasted disgusting in the past, and a different type of memory for food that was good to eat. The amygdala, a small almond-shaped object that is part of the limbic system, plays a central role in remembering whether something should be approached or avoided. The amygdala (and its associated networks) are believed to activate proportionally to the strength of an emotional response.

The limbic system can processes stimuli before it reaches conscious awareness. one study showed that subliminally presented nonsense words that were similar to threatening words, were still categorized as possible threats by the amygdala (Naccache et al, 2005). Brainstem – Limbic networks process threat and reward cues within a fifth of a second, providing you with ongoing nonconscious intuition of what is meaningful to you in every situation of your daily life (Gordon et al. Journal of integrative Neuroscience, Sept 2008). Such studies show that the approach-avoid response drives attention at a fundamental level – nonconsciously, automatically and quickly. It is a reflexive activity.

it is easy to see that the ability to recognizing primary rewards and threats, such as good versus poisonous food, would be important to survival and thus a part of the brain. Social neuroscience shows us that the brain uses similar circuitry for interacting with the social world. Lieberman and Eisenberger explore this finding in detail in a paper in this journal entitled ‘The Pains and Pleasures of Social Life’ (Lieberman & Eisenberger, 2008).

² David Rock's SCARF model is aimed at modeling motivation as it relates to social experiences. However, for the purpose of this post, and having used the model as a frame to evaluate motivation for years now, it's widely applicable to most anything. This surely has to do with the universal truth that human beings are social animals and nearly everything anyone does either directly or indirectly involves other people.