The Anxious Generation

A book review of Jonathan Haidt's The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, including selected quotes and material.

"The kids aren't alright," and it's on us — parents, adults, leaders, all — to wake up from our collective inaction, see what's happening, and act.

This is the point of The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, Jonathan Haidt's latest book, released March 26, 2024. Haidt tapped into the zeitgeist: Anxious jumped to #3 on Amazon across all books and #1 on the NYT non-fiction list within two weeks.

The Anxious Generation is a timely book that, if nothing else, will drive awareness regarding the confounding problem of kids today: Harm is done to kids when they grow up shielded from real world experience.

This is a heavy review, but you can take what you want from it:

➡ TL;DR review + recommendation 👀

➡ Full-blown review ⭐️

➡ The Anxious Generation Quotes 🐶 (I dog-eared ⅓ of it)

Here we go.

TL;DR review + recommendation

Giving kids smartphones, and especially social media, is not good for them.

(Smartphones and social media aren't good for any of us, but Haidt is saving this topic for another day.)

It doesn't have to be this way. There are bottoms-up and top-down solutions worth considering to help restore healthy childhood development. Haidt suggests many of them. My big a-ha from the book is this:

Kids thrive when they experience life directly. Safetyism — shielding kids from real-world experienced — makes kids fragile. Internet-mediated childhood blocks kids from real-life experiences and exposes kids to harms, making kids mentally unwell. Help kids by removing the blockers of real-world experiences — so that kids have the opportunity to grow and thrive.

The Anxious Generation is imperfect, but the best book to read for a primer on the harms to kids of a phone-based life — plus insight into the benefits of experience. Finally, Haidt offers many suggestions for how to fix the problem, some are easy to implement at the local level. Others not so much (read the full review).

The Internet is everywhere and inescapable. We must figure out how to live, work, parent, find meaning, and relate despite it.

Recommendations

👉 If you have kids, read this book. Talk about it with other parents. There's much you can do today to help your kids.

👉 If you are concerned about how technology (and media) harms people, read this book.

👉 Educate yourself on Agenda-Setting Theory and WYSIATI. (Because this stuff is harming us adults, too.)

👉 Read Amusing Ourselves to Death and Technopoly — two books by Neil Postman.

The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness

From New York Times bestselling coauthor of The Coddling of the American Mind, an essential investigation into the collapse of youth mental health—and a plan for a healthier, freer childhood.

My full review

In The Anxious Generation, Haidt shares how depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicide for children (and adolescents, age 0–20) all began rising around 2010, which coincides with the widespread adoption of a "phone-based life."

(Phone-based includes all Internet connected devices, with a special focus on mobile devices.)

Haidt details how girls are especially harmed by smartphone adoption, and boys aren't doing great either. For example, both groups have seen a ~150% increase in depression since 2010, with a whopping 3 out of 10 girls having one major depressive episode in the last year as of 2021. For boys this is 1 out of 10 in 2021 — where girls were before 2010. In all cases, the always-on, always-available Internet displaces experiences and relationships that kids need to become strong and functional people.

If you're looking for the data on this, you will find it in this book. You can also check out Jean Twenge's iGen. (I have.) In both cases, the data — i.e. suggesting harm from smartphones and social media — will confirm your bias.

Notably, Haidt also addresses counterarguments to his argument in the book.

If you want an argument that The Anxious Generation is not "supported by science," enjoy this review by Candice Odgers at Nature.com, who I'm left to assume lives in an ivory tower — and needs more real world experience.

How smartphones and social media harm kids

The Anxious Generation also gets into the many ways kids are harmed by smartphones and social media, including how apps are designed to hijack attention and drive addictive behaviors.

Haidt covers most all the angles of harm for both girls and boys, providing a nuanced look at each group.

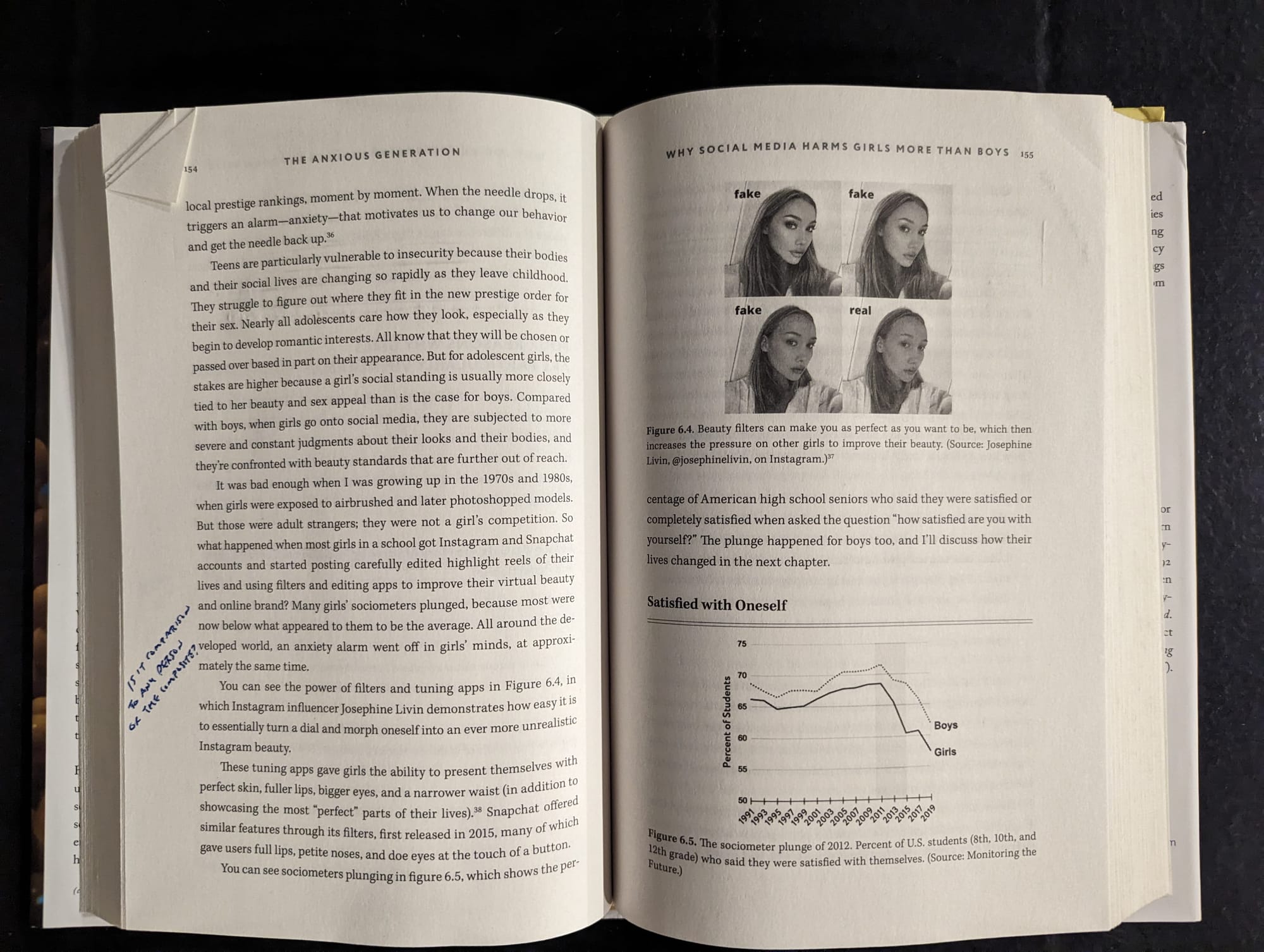

For girls, he shares that, "Girls who say that they spend five or more hours each weekday on social media are three times as likely to be depressed as those who report no social media time."

Haidt argues that social media is more harmful to girls than boys because girls (and women) tend be more focused on connection with others. Haidt calls this "communion striving" and contrasts it to "agency striving," which tends to be a larger focus for boys and women.

For boys, this agency striving is exploited through video games. Haidt writes, "From the beginning of the digital age, the tech industry has found ever more compelling ways to help boys do the things they want to do without having to take social and physical risks that were once needed to satisfy those desires."

Haidt does not find "clear evidence that would support a blanket warning to parents to keep their boys entirely away from video games." However, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and Haidt sees two "major harms" associated with video games as the impact heavy video game users — dependency and, again, opportunity cost (more on this below).

Missing harms

Missing from the discussions of harms in The Anxious Generation is how the Internet tends to silo boys and girls from each other. This is hinted at for boys as Haidt mentions boys can satisfy physical needs "risk-free" through access to pornography, for example. However, the harm of siloed sexes is largely skipped.

For example, when boys compete in private, outside the view of the opposite sex, what does that mean for their drive to achieve greater agency and status? How does filtered and exaggerated sexuality favored by algorithms on social media impact the actions of girls — actions that are done in private but seen asymmetrically in public by everyone?

These public vs. private aspects of sexual development surely have an impact, but what is it? How is gender development influenced in the absence of real-world models, influences, and experiences?

Another missing harm is that caused by narrowly focused attention — i.e. constraining reality to whatever algorithms deem important and salient, which is itself highly personalized to each user and privately experienced. For this harm, I'd have liked Haidt to explore the agenda-setting and WYSIATI impacts of apps (See my primer on Robert Cialdini's Agenda-setting theory as well as Daniel Kahneman's WYSIATI).

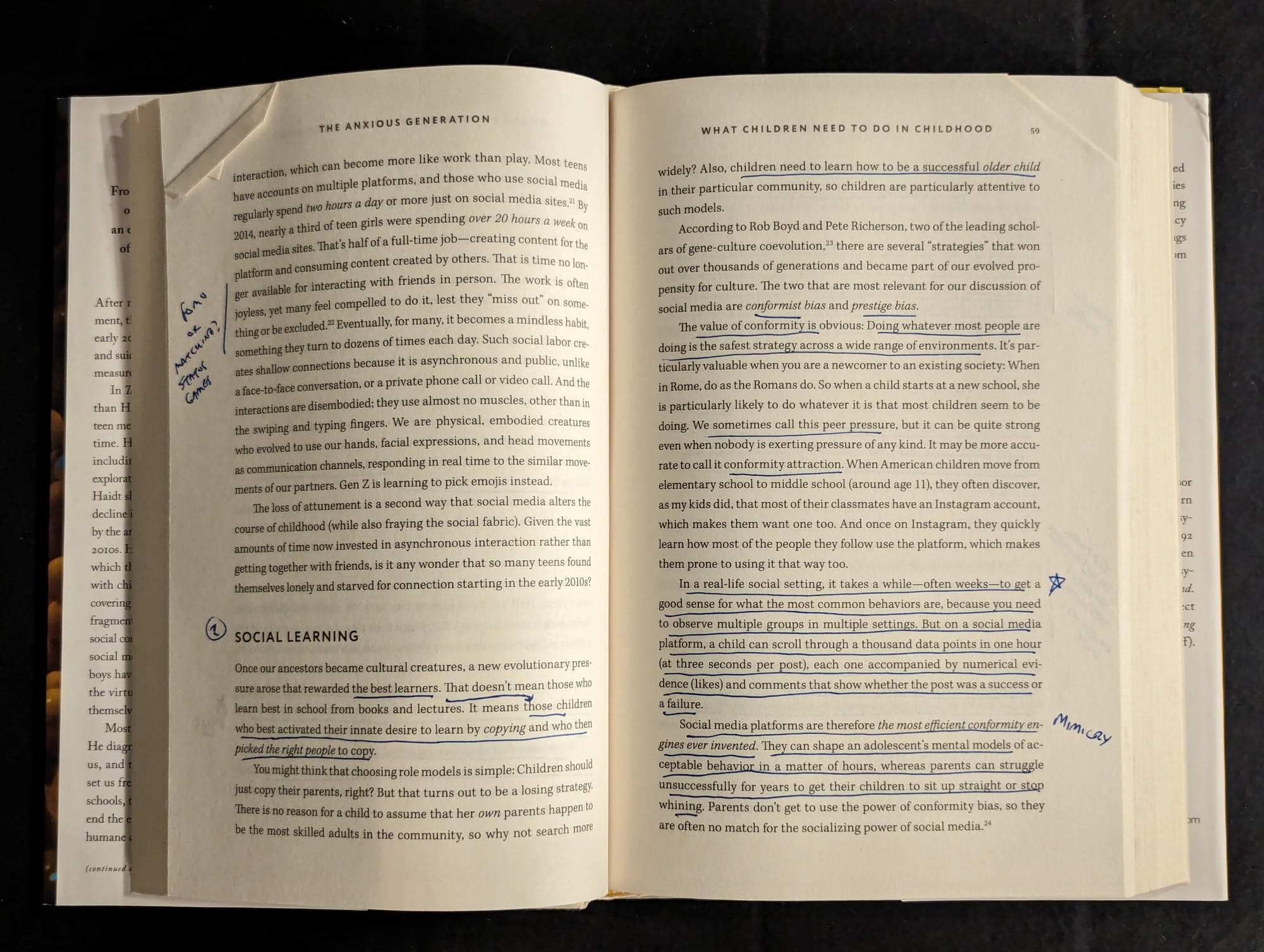

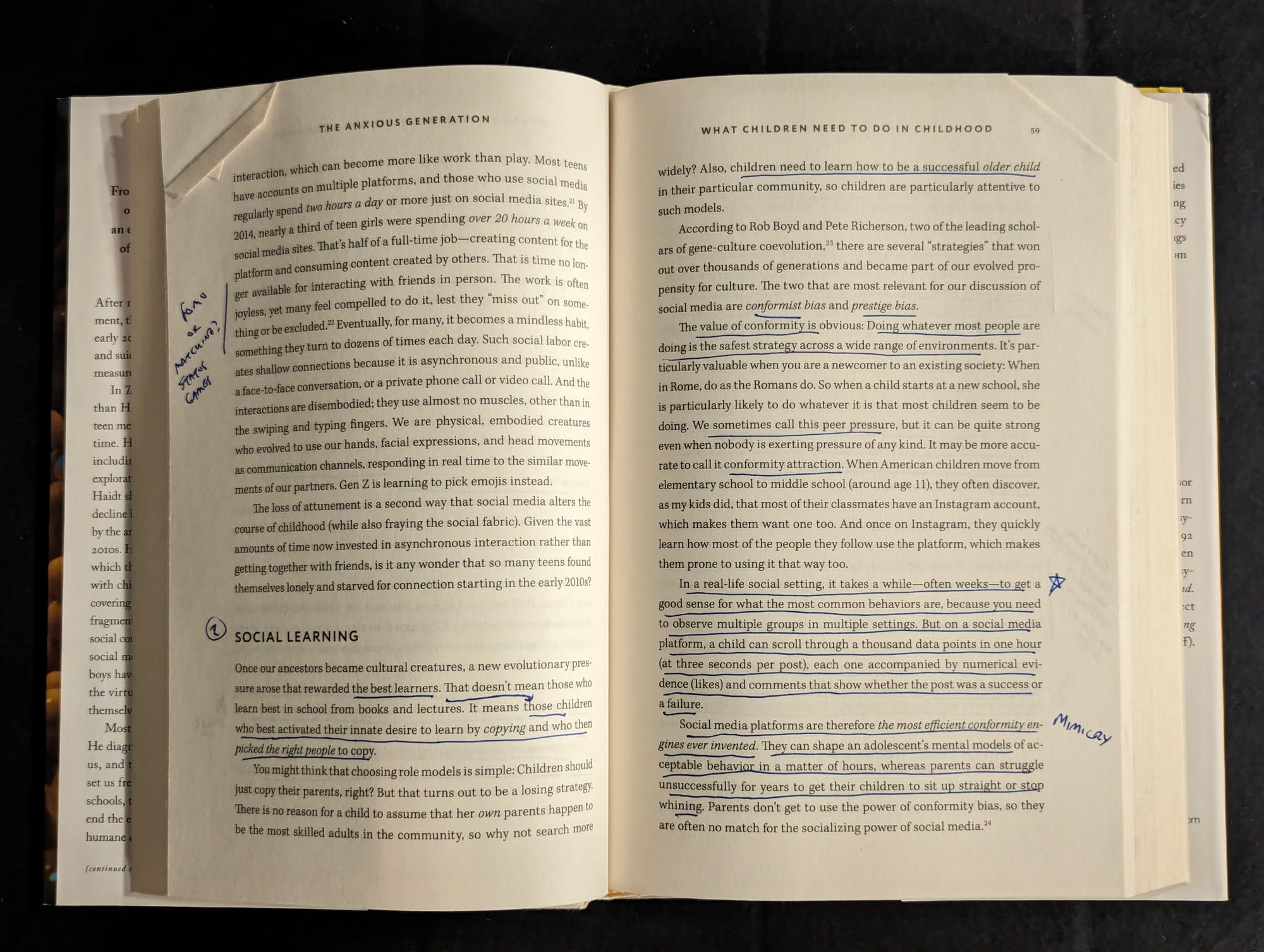

I appreciate Haidt getting into social learning. He approaches the subject through the lens of conformity and prestige bias. I believe mimicry could have been covered more explicitly, but Haidt does discuss aspects such as "sociogenic epidemics" and outbreaks of Tourette's syndrome (See specific quotes at the end of this review). However, he hedges on related questions of gender expression.

If you're not familiar with any of these harms, The Anxious Generation offers an excellent primer.

Overprotection and underprotection

Central to the structure of The Anxious Generation is Haidt's central claim, found in the beginning:

My central claim in this book is that these two trends—overprotection in the real world and underprotection in the virtual world—are the major reasons why children born after 1995 became the anxious generation.

Because of this claim, Haidt must balance opposing positions throughout the book.

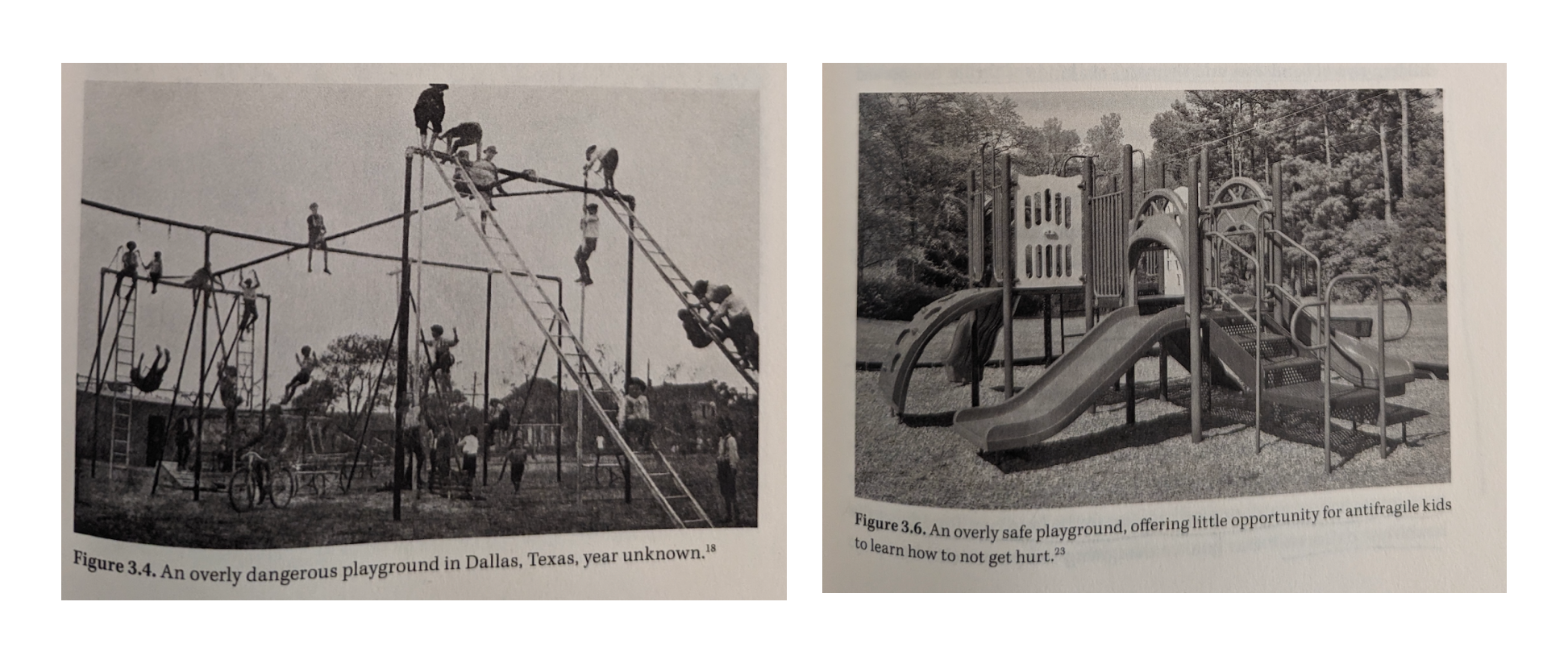

He must discuss the harm of overprotection in real, non-virtual life, which leads him to detail the importance of play, risk-taking, and anti-fragility for child development.

Haidt must also explore the harm of underprotection online, which he does by detailing the general harms (addiction, social and sleep deprivation, and attention fragmentation) as well the specific harms to girls and boys.

Haidt is using his underprotection framing to set up policy recommendations of protection toward the end of the book. Yes, Haidt is right: Kids are underprotected online and overprotected in "IRL;" however, the over/under dichotomy distracts from the his more poignant argument:

Kids need real world experience, and they aren't getting it.

The problem with protection

Haidt writes, "Experience, not information, is the key to emotional development," and later, "... we might refer to smartphones and tablets in the hands of children as experience blockers."

Yes! This is it!

The experience framing is fundamental to why the Internet is harmful — and not just for children but for everyone. Just as overprotection in the real world blocks experience, so too do smartphones. Smartphones prevent children from getting the experiences they need to learn in the best way they can — through life in the real world.

Haidt offers us a powerful description of real world experiences, too, writing:

"When I talk about the 'real world,' I am referring to relationships and social interactions characterized by four features that have been typical for millions of years:

"1. They are embodied, meaning that we use our bodies to communicate, we are conscious of the bodies of others, and we respond to the bodies of others both consciously and unconsciously.

"2. They are synchronous, which means they are happening at the same time, with subtle cues about timing and turn taking.

"3. They involve primarily one-to-one or one-to-several communication, with only one interaction happening at a given moment.

"4. They take place within communities that have a high bar for entry and exit, so people are strongly motivated to invest in relationships and repair rifts when they happen."

Much could be written about these four features of the real world, and I applaud Haidt for making them explicit. Every virtual substitute for the real world should be examined by asking how it falls short of these four criteria.

The "overprotection versus underprotection" dichotomy feels distracting. Instead, framed through experience, we see that online experiences rob kids of real world experience, regardless of levels of protection. Yes, with no protection the harm is even worse, but that's at least a bit like saying heroin becomes okay in the right amounts.

This leads me to one rule of thumb worth remembering:

Kids need real world experiences, and there is no virtual substitute. Zoom, Facetime, video calling, etc., are as good as it gets online — which is not good enough. If you want healthier kids (and a healthier life for yourself), shift as much experience to the real world as you can by avoiding the Internet as much as possible. Give kids the opportunity to be kids without meddling from adults.

From there, once you inevitably allow kids to have smartphones:

Foster a less harmful (though still harmful!) online experience by encouraging smart policies like no-phone schools and some modicum of responsibility for technology companies. It's always on us to learn how to use smartphones and Internet access responsibly, and to teach kids how to do likewise.

That collective action problem

I know. It's not that easy.

The biggest problem in addressing a phone-based life is "collective action." If no one is outside playing, no kid will want to go outside. When the only way to communicate with friends is through chat on Apple Messages, of course your kid will need an iPhone — otherwise they won't be able to communicate. This is just one example where kids rightly believe they are left out — there are countless others from not having access to video game platforms to Snapchat or Instagram.

Haidt sums up the collective action problem thusly:

"Once a few students get smartphones and social media accounts, the other students put pressure on their parents, putting them into a trap as well. It's painful for parents to hear their children say.'Everyone else has smartphone. If you don't get me one, I'll be excluded from everything.' (Of course, 'everyone' may just mean "some other kids.") Few parents want their preteens to disappear into a phone, but the vision of their child being a social outcast is even more distressing. Many parents therefore give in and buy their child a smartphone at age 11, or younger. As more parents relent, pressure grows on the remaining kids and parents, until the community reaches a stable but unfortunate equilibrium: Everyone really does have a smartphone, everyone disappears into their phones, and the play-based childhood is over.

How do you get everyone, everywhere to change at once? How do we "roll back" our overly virtual way of existing?

As alluded to earlier, Haidt offers specific recommendations to address the collective action problem, with his four reforms being to make 16 the age of Internet adulthood, asserting a duty of care (regulatory), age verification (regulatory), and encouraging phone-free schools. He also proposes a handful of recommendations for parents to encourage more real-world experience.

Aside from the bottoms-up solutions for parents, I'm concerned that trying to fix underprotection online through large-scale policies will create new problems. For one, what's to stop attempts at protection online from ending up just like the "safetyism" thwarting kids in the real world today?

In theory, policy will help solve the problem. In practice, it will create new problems. What's to stop the technology companies from nudging the regulation to their own benefit?

We've seen this before.

Haidt's top-down policy recommendations should be considered carefully, and especially his recommendations that would require large-scale intervention and put free speech at risk. (For more on this, I point you to Haidt's Coddling of the American Mind co-author, Greg Lukianoff, who shares his First Amendment concerns.)

As for recommendations like no phones at school? Yes, please! More real world play opportunities? Absolutely. Parents should talk about The Anxious Generation and take action to build a groundswell.

We need new norms as a society for how to manage technology in our lives. It's time we start finding them.

"The phone-based life produces spiritual degradation, not just in adolescents, but in all of us."

– Jon Haidt

The Anxious Generation

Screens are blockers of real-world experiences.

— Lenore Skenazy (@FreeRangeKids) June 16, 2024

So are the beliefs that:

1- Kids are in constant danger if not supervised.

2- Adult-run activities are best.

3- Kids only learn when being "taught."

Trust kids w/ more real world independence & screens beckon less.#LetGrow https://t.co/PQX0txiPYk

Conclusion

Policy recommendation concerns aside, I believe Haidt takes the most important step in addressing the collective action problem:

He uses The Anxious Generation to generate awareness and discussion about this clear and present danger to society.

I've spent the bulk of my career in digital media. I've worked, researched, studied, and written on related topics for fifteen years (See below for my qualifications for writing this review). Based on my experience, I see The Anxious Generation as that critical first step toward raising awareness on the downsides of an Internet-mediated life. It's worth the read. Buy it. Talk about it. Share it.

Though the book focuses on children, Haidt is clearly using Anxious to set the stage to address the big picture problem for all of us — and in the near future. Look to his substack After Babel to stay on top of his work here.

I hope The Anxious Generation is read widely. As Haidt concludes, "You shouldn't have to compete for your students' attention with the entire Internet."

This is how big things things start.

Thank you, Jonathan Haidt, Zack Rausch, Lenore Skenazy, and the broader team behind this important book.

If you're into that kind of thing, subscribe! (It's free.)

My qualifications for writing this review

My name is Justin Owings, and I'm a "geriatric" Millennial father of three. I have two girls aged twelve and fourteen. I have an eight-year-old boy.

For over two decades I've worked in content creation, communications, and digital marketing. A third of that time was spent researching digital trends for Google, specifically researching changes in time spent with media as well as attention-based business models.

Over the last fifteen years I've written on how the Internet affects us, covering confirmation bias, content proliferation, attention, digital isolation, smartphones and human nature, broken social networks, "going cyborg," how apps are traps, and even examining cults and brainwashing.

I've supplemented my personal and professional experiences with studying works directly related to parenting and kids, including reading books by Lenore Skenazy, John Taylor Gatto, Peter Gray, Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish, John Gall, and Virginia Satir, among others.

In addition to my work in digital marketing, I've studied communication, persuasion, propaganda, therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, stoicism, media, negotiation, and even hypnosis.

I've also read specific background works mentioned in this book, e.g. Jean Twenge's iGen, Nir Eyal's Hooked, and Joseph Henrich's The Secret of Our Success.

Finally, I have also read The Coddling of the American Mind by Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff — but not Haidt's The Righteous Mind or The Happiness Hypothesis.

Quotes from The Anxious Generation

Below are selected quotes from Jonathan Haidt's book The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. Click each headline to toggle the quote.

All quotes are in chronological order from the book with page numbers noted from the hardback. Emphasis generally added by R-ght with italics preserved from the book.

The age of "internet adulthood"

p. 4

"In the United States, which ended up setting the norms for most other countries, the main prohibition is the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), enacted in 1998. It requires children under 13 to get parental consent before they can sign a contract with a company (the terms of service) to give away their data and some of their rights when they open an account. That set the effective age of 'internet adulthood' at 13, for reasons that had little to do with children's safety or mental health. But the wording of the law doesn't require companies to verify ages; as long as a child checks a box to assert that she's old enough (or puts in the right fake birthday), she can go almost anywhere on the internet without her parents' knowledge or consent. In fact, 40% of American children under 13 have created Instagram accounts, yet there has been no update of federal laws since 1998."

The Anxious Generation's definition of Gen Z goes beyond Gen Z

p. 5

"This book tells the story of what happened to the generation born after 1995, popularly known as Gen Z, the generation that follows the millennials (born 1981 to 1995). Some marketers tell us that Gen Z ends with the birth year 2010 or so, and they offer the name Gen Alpha for the children born after that, but I don't think that Gen Z—the anxious generation—will have an end date until we change the conditions of childhood that are making young people so anxious."

The need to manage your online brand

p. 6

"Gen Z became the first generation in history to go through puberty with a portal in their pockets that called them away from the people nearby and into an alternative universe that was exciting, addictive, unstable, and—as I will show unsuitable for children and adolescents. Succeeding socially in that universe required them to devote a large part of their consciousness—perpetually—to managing what became their online brand."

The shift from play-based childhood to phone-based childhood — and Haidt's definition of childhood for the book

pp. 7–8

"I propose that we view the late 1980s as the beginning of the transition from a 'play-based childhood' to a 'phone-based childhood,' a transition that was not complete until the mid-2010s, when most adolescents had their own smartphone. I use 'phone-based' broadly to include all of the internet-connected personal electronics that came to fill young people's time, including laptop computers, tablets, internet-connected video game consoles, and, most important, smartphones with millions of apps.

"When I speak of a play-based or phone-based 'childhood,' I'm using that term broadly too. I mean it to include both children and adolescents.

...

- Children: 0 through 12.

- Adolescents: 10 through 20.

- Teens: 13 through 19.

- Minors: Everyone who is under 18. I'll also use the word 'kids' some-times, because it sounds less formal and technical than 'minors.'"

Four features of the "real world"

p. 9

"When I talk about the 'real world,' I am referring to relationships and social interactions characterized by four features that have been typical for millions of years:

- They are embodied, meaning that we use our bodies to communicate, we are conscious of the bodies of others, and we respond to the bodies of others both consciously and unconsciously.

- They are synchronous, which means they are happening at the same time, with subtle cues about timing and turn taking.

- They involve primarily one-to-one or one-to-several communication, with only one interaction happening at a given moment.

- They take place within communities that have a high bar for entry and exit, so people are strongly motivated to invest in relationships and repair rifts when they happen.

Four features of the "virtual world"

pp. 9–10

"In contrast, when I talk about the 'virtual world,' I am referring to relationships and interactions characterized by four features that have been typical for just a few decades:

- They are disembodied, meaning that no body is needed, just lan-guage. Partners could be (and already are) artificial intelligences (AIs).

- They are heavily asynchronous, happening via text-based posts and comments. (A video call is different; it is synchronous.)

- They involve a substantial number of one-to-many communications, broadcasting to a potentially vast audience. Multiple interactions can be happening in parallel.

- They take place within communities that have a low bar for entry and exit, so people can block others or just quit when they are not pleased. Communities tend to be short-lived, and relationships are often disposable.

The blurry difference between the "real world" and "virtual world"

p. 10

"In practice, the lines blur. My family is very much real world, even though we use FaceTime, texting, and email to keep in touch. Conversely, a relationship between two scientists in the 18th century who knew each other only from an exchange of letters was closer to a virtual relation-ship. The key factor is the commitment required to make relationships work. When people are raised in a community that they cannot easily escape, they do what our ancestors have done for millions of years: They learn how to manage relationships, and how to manage themselves and their emotions in order to keep those precious relationships going."

Four reforms proposed by Haidt

1. No smartphones before high school. Parents should delay children's entry into round-the-clock internet access by giving only basic phones (phones with limited apps and no internet browser) before ninth grade (roughly age 14).

2. No social media before 16. Let kids get through the most vulnerable period of brain development before connecting them to a firehose of social comparison and algorithmically chosen influencers.

3. Phone-free schools. In all schools from elementary through high school, students should store their phones, smartwatches, and any other personal devices that can send or receive texts in phone lockers or locked pouches during the school day. That is the only way to free up their attention for each other and for their teachers.

4. Far more unsupervised play and childhood independence. That's the way children naturally develop social skills, overcome anxiety, and become self-governing young adults.

Internalizing vs. externalizing disorders

p. 25

"The first clue is that the rise is concentrated in disorders related to anxiety and depression, which are classed together in the psychiatric category known as internalizing disorders. These are disorders in which a person feels strong distress and experiences the symptoms inwardly. The person with an internalizing disorder feels emotions such as anxiety, fear, sadness, and hopelessness. They ruminate. They often withdraw from social engagement.

"In contrast, externalizing disorders are those in which a person feels distress and turns the symptoms and responses outward, aimed at other people. These conditions include conduct disorder, difficulty with anger management, and tendencies toward violence and excessive risk-taking. Across ages, cultures, and countries, girls and women suffer higher rates of internalizing disorders, while boys and men suffer from higher rates of externalizing disorders. That said, both sexes suffer from both, and both sexes have been experiencing more internalizing disorders and fewer externalizing disorders since the early 2010s."

When anxiety becomes a disorder

p. 28

"It is healthy to be anxious and on alert when one is in a situation where there really could be dangers lurking. But when our alarm bell is on a hair trigger so that it is frequently activated by ordinary events—including many that pose no real threat—it keeps us in a perpetual state of distress. This is when ordinary, healthy, temporary anxiety turns into an anxiety disorder."

Social death

p. 28

"Our evolutionary advantage came from our larger brains and our capacity to form strong social groups, thus making us particularly attuned to social threats such as being shunned or shamed. People—and particularly adolescents—are often more concerned about the threat of 'social death' than physical death."

What anxiety feels like

p. 28

"Anxiety affects the mind and body in multiple ways. For many, anxiety is felt in the body as tension or tightness and as discomfort in the abdomen and chest cavity. Emotionally, anxiety is experienced as dread, worry, and, after a while, exhaustion. Cognitively, it often becomes difficult to think clearly, pulling people into states of unproductive rumination and provoking cognitive distortions that are the focus of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), such as catastrophizing, overgeneralizing, and black-and-white thinking. For those with anxiety disorders, these distorted thinking patterns often elicit uncomfortable physical symptoms, which then induce feelings of fear and worry, which then trigger more anxious thinking, perpetuating a vicious cycle."

The outsized effect on girls seen through rate of self-harm

p. 31

"The rate of self-harm for these young adolescent girls nearly tripled from 2010 to 2020. The rate for older girls (ages 15-19) doubled, while the rate for women over 24 actually went down during that time (see online supplement)." So whatever happened in the early 2010s, it hit preteen and young teen girls harder than any other group. This is a major clue."

Data on smartphone ownership

pp. 33–34

"There are several sources for data on the early smartphone era. A 2012 report on cell phone ownership from Pew Research found that in 2011, 77% of American teens had a phone but just 23% had a smartphone. That means most teens had to access social media using a computer. Often it was their parents' computer or the family computer, so they had limited privacy and access, and there was no easy way to get online when away from home. In the United States, laptop computers became increasingly common in this period, as did high-speed internet, so some teens started gaining increased access to the internet even before they got their own smartphones.

"But it wasn't until teens got smartphones that they could be online all the time, even when away from home. According to a survey of U.S. parents conducted by the nonprofit Common Sense Media, by 2016, 79% of teens owned a smartphone, as did 28% of children between the ages of in 8 and 12.

"As adolescents got smartphones, they began spending more time in the virtual world. A 2015 Common Sense report found that teens with a social media account reported spending about two hours a day on social media, and teens overall reported spending an average of nearly seven hours a day of leisure time (not counting school and homework) on screen media, which includes playing video games and watching videos on Netflix, YouTube, or pornography sites. A 2015 report by Pew Research confirms these high numbers: One out of every four teens said that they were online "almost constantly." By 2022, that number had nearly doubled, to 46%."

Counterargument to anxiety and depression from world events

p. 36

"Even if we were to accept the premise that the events from 9/11 through the global financial crisis had substantial effects on adolescent mental health, they would have most heavily affected the millennial generation (born 1981 through 1995), who found their happy childhood world shattered and their prospects for upward mobility reduced. But this did not happen; their rates of mental illness did not worsen during their teenage years. Also, had the financial crisis and other economic concerns been major contributors, adolescent mental health in the United States would have plummeted in 2009, during the darkest year of the financial crisis, and it would have improved throughout the 2010s as the unemployment rate fell, the stock market rose, and the economy heated up. Neither of these trends is borne out in the data."

Delaying development to learn as much as possible

p. 51

"Our planet-changing trait was the ability to learn from each other and tap into the common pool of knowledge our ancestors and community had stored. Chimpanzees do very little of this. Human childhood extended to give children time to learn."

Editorial note: See also Joseph Henrich's book The Secret of Our Success.

Peter Gray's definition of "free play"

p. 52

"Gray defines 'free play' as 'activity that is freely chosen and directed by the participants and undertaken for its own sake, not consciously pursued to achieve ends that are distinct from the activity itself.'"

Conformity bias

p. 59

"The value of conformity is obvious: Doing whatever most people are doing is the safest strategy across a wide range of environments. ...

"In a real-life social setting, it takes a while—often weeks—to get a good sense for what the most common behaviors are, because you need to observe multiple groups in multiple settings. But on a social media platform, a child can scroll through a thousand data points in one hour (at three seconds per post), each one accompanied by numerical evidence (likes) and comments that show whether the post was a success or a failure.

"Social media platforms are therefore the most efficient conformity engines ever invented. They can shape an adolescent's mental models of acceptable behavior in a matter of hours, whereas parents can struggle unsuccessfully for years to get their children to sit up straight or stop whining. Parents don't get to use the power of conformity bias, so they are often no match for the socializing power of social media."

Prestige bias

p. 60

"... there's an important learning strategy that goes beyond copying the majority: Detect prestige and then copy the prestigious. The major work on prestige bias was done by the evolutionary anthropologist Joe Henrich who was a student of Rob Boyd's. Henrich noted that the social hierarchies of nonhuman primates are based on dominance—the ability, ultimately, to inflict violence on others. But humans have an alternative ranking system based on prestige, which is willingly conferred by people to those they see as having achieved excellence in a valued domain of activity, such as hunting or storytelling back in ancient times.

"... Henrich argues that the reason people become so deferential (starstruck) toward prestigious people is that they are motivated to get close to prestigious people in order to maximize their own learning and raise their own prestige by association.

"... Platform designers in Silicon Valley directly targeted this psychological system when they quantified and displayed the success of every post (likes, shares, retweets, comments) and every user, whose followers are literally called followers. Sean Parker, one of the early leaders of Facebook, admitted in a 2017 interview that the goal of Facebook's and Instagram's founders was to create 'a social-validation feedback loop ... exactly the kind of thing that a hacker like myself would come up with because you're exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.' But when the programmers quantified prestige based on the clicks of others. they hacked our psychology in ways that have been disastrous for young people's social development."

Discover mode and defend mode

p. 69

"The variability of our environments shaped and refined older brain networks into two systems that are specialized for those two kinds of situations. The behavioral activation system (or BAS) turns on when you detect opportunities, such as suddenly coming across a tree full of ripe cherries when you and your group are hungry. You're flooded with positive emotions and shared excitement, your mouths may begin to water, and everyone is ready to go! I'll give BAS a more intuitive name: discover mode.

"The behavioral inhibition system (BIS), in contrast, turns on when threats are detected, such as hearing a leopard roar nearby as you're picking those cherries. You all stop what you are doing. Appetite is suppressed as your bodies flood with stress hormones and your thinking turns entirely to identifying the threat and finding ways to escape it. I'll refer to BIS as defend mode. For people with chronic anxiety, defend mode is chronically activated."

Nassim Taleb's concept of antifragile

p. 73

"Taleb coined the word 'antifragile' to describe things that actually need to get knocked over now and then in order to become strong. I used the word 'things,' but there are very few inanimate objects that are antifragile. Rather, antifragility is a common property of complex systems that were designed (by evolution, and sometimes by people) to function in a world that is unpredictable."

See Nassim Taleb's book Antifragile.

The harms of eliminating risky play

p. 80

"What parent wants to take any risks with their child? But the harms of eliminating all risky outdoor play are substantial. While writing this chapter, I met with Mariana Brussoni, a play researcher at the University of British Columbia. Brussoni guided me to research showing that the risk of injury per hour of physical play is lower than the risk per hour of playing adult-guided sports, while conferring many more developmental benefits (because the children must make all choices, set and enforce rules, and resolve all disputes). Brussoni is on a campaign to encourage risky outdoor play because in the long run it produces the healthiest children."

The difference between friendships on phones versus real life

pp. 81–82

"I see few indications that a phone-based childhood develops antifragility. Human childhood evolved in the real world, and children's minds are"expecting" the challenges of the real world, which is embodied, synchronous, and one-to-one or one-to-several, within communities that endure. For physical development they need physical play and physical risk-taking. Virtual battles in a video game confer little or no physical beneft, For social development they need to learn the art of friendship, which is embodied; friends do things together, and as children they touch, hug, and wrestle. Mistakes are low cost, and can be rectified in real time. Moreover, there are clear embodied signals of this rectification, such as an apology with an appropriate facial expression. A smile, a pat on the back, or a handshake shows everyone that it's okay. both parties are ready to move on and continue playing, both are developing their skills of relationship repair, In contrast, as young people move their social relationships online, those relationships become disembodied, asynchronous, and sometimes disposable. Even small mistakes can bring heavy coststha viral world where content can live ion ver and everyone cana. costistakes can be met with intense criticism by multiple individuals with whom one has no underlying band. Apologies are often mocked and any signal of re-acceptance can be mixed or vague. Instead of gaining an experience of social mastery, a child is often left with a sense of social incompetence, loss of status, and anxiety about future social interactions."

Rites of passage

p. 100

"Despite the enormous variation in human cultures and gender roles, there is a common structure to puberty rites because they are all trying to do the same thing: Transform a girl into a woman or a boy into a man who has the knowledge, skills, virtues, and social standing to be an effective member of the community, soon to be ready for marriage and par-enthood. in 1909, the Dutch-French ethnographer Arnold van Gennep noted that rites of passage around the world take the child through the same three phases. First, there is a separation phase in which young adolescents are removed from their parents and their childhood habits. Then there is a transition phase, led by adults other than the parents who guide the adolescent through challenges and sometimes ordeals. Finally, there is a reincorporation phase that is usually a joyous celebration by the community (including the parents), welcoming the adolescent as a new member of adult society, even though he or she will often receive years of further instruction and support."

Summary of the history of smartphones and apps

p. 115

"When Steve Jobs announced the first iPhone in June 2007, he described it as a widescreen iPod with touch controls, a revolutionary mobile phone, and breakthrough internet communication device. The first iteration of the iPhone was quite simple by today's standards, and I have no reason to believe it was harmful to mental health. I bought one in 2008 and found it to be a remarkable digital Swiss Army knife, full of tools I could call on when I needed them. It even had a flashlight! It was not designed to be addictive or to monopolize my attention.

"This soon changed with the introduction of software development kits, which allowed third-party apps to be downloaded onto mobile devices. This revolutionary move culminated in the launch of the App Store by Apple in July 2008, starting with 500 apps available. Google followed suit with the Android Market in October 2008, which was rebranded and expanded into Google Play in 2012. By September 2008, the Apple App Store had grown to hold more than 3,000 apps, and by 2013 it had more than 1 million. The Google Play store grew right alongside Apple, reaching 1 million apps in 2013.

"The opening of smartphones to third-party apps led to fierce competition among companies large and small to create the most engaging mobile apps. The winners of this race were often those that adopted free-to-use, advertising-based business models because few consumers would pay $2.99 for an app if a competitor offered one for free. This proliferation of advertising-driven apps caused a change in the nature of time spent using a smartphone. By the early 2010s, our phones had transformed from Swiss Army knives, which we pulled out when we needed a tool, to platforms upon which companies competed to see who could hold on to eyeballs the longest."

Four features of social media platforms

pp. 116–117

"Social media has evolved over time, but there are at least four major features common to the platforms we generally think of as being clear examples of social media: user profiles (users can create individual profiles where they can share personal information and interests); user-generated content (users create and share a variety of content to a broad audience, including text posts, photos, videos, and links); networking (users can connect with other users by following their profiles, becoming friends, or joining the same groups); and interactivity (users interact with each other and with the content they share; interactions may include liking, commenting, sharing, or direct messaging). The prototypical media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok, Reddit, and Linkedin share all four features, as does YouTubes (even though Youtube is more widely used as the world's video library than for its social features) and also the now popular video game streaming platform Twitch. Even modern adult-content sites, like OnlyFans, have adopted these four features. On the other hand, messaging apps such as WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger do not have all four features and while they are certainly social, they would not be considered social media."

Editorial note: Important to note that chat apps tend to be symmetrical platforms for communication — not "one-to-any."

Early advances in social media technology

p. 117

"First and foremost, in 2009, Facebook introduced the 'like' button and Twitter introduced the 'retweet' button. Both of these innovations were then widely copied by other platforms, making viral content dissemination possible. These innovations quantified the success of every post and incentivized users to craft each post for maximum spread, which sometimes meant making more extreme statements or expressing more anger and disgust. At the same time, Facebook began using algorithmically curated news feeds, which motivated other platforms to join the race and curate content that would most successfully hook users. Push notifications were released in 2009, pinging users with notifications throughout the day. The app store brought new advertising-driven platforms to smartphones. Front-facing cameras (2010) made it easier to take photos and videos of oneself, and the rapid spread of high-speed internet (reaching 61% of American homes by January 20109) made it easier for everyone to consume everything quickly."

Why 2010 began The Great Rewiring

"By the early 2010s, social "networking" systems that had been structured (for the most part) to connect people turned into social media 'platforms' redesigned (for the most part) in such a way that they encouraged one-to-many public performances in search of validation, not just from friends but from strangers. Even users who don't actively post are affected by the incentive structures these apps have designed.

"These changes explain why the Great Rewiring began around 2010 and why it was largely complete by 2015. Children and adolescents, who were increasingly kept at home and isolated by the national mania for overprotection, found it ever easier to turn to their growing collection of internet-enabled devices, and those devices offered ever more attractive and varied rewards. The play-based childhood was over; the phone-based childhood had begun."

"Six to eight hours per day" across leisure activities on screens

p. 119

"Those numbers -six to eight hours per day are what teens spend on all screen-based leisure activities. Of course, children were already spending a lot of their time watching TV and playing video games before the smartphone and internet became parts of their daily lives. Long-running studies of American adolescents show that the average teen was watching a little less than three hours per day of television in the early 1990s. As most families gained dial-up access to the internet during that decade, followed by high-speed internet in the 2000s, the amount of time spent on internet-based activities increased, while time spent watching TV decreased. Kids also began to spend more time playing video games and less time reading books and magazines. Putting it all together, the Great Rewiring and the dawn of the phone-based childhood seem to have added two to three hours of additional screen-based activity, on average, to a child's day, compared with life before the smartphone."

The Hooked model

p. 132

"There is no off-ramp in an app with a bottomless feed; there is no signal to stop.

"These first three steps [of the Hook Model by Nir Eyal — i.e. Trigger, Action, Variable Reward] are classic behaviorism. They deploy operant conditioning as taught by B. F. Skinner in the 1940s. What the Hooked model adds for humans, which was not applicable for those working with rats, was the fourth step: investment. Humans can be offered ways to put a bit of themselves into the app so that it matters more to them. The girl has already filled out her profile, posted many photos of herself, and linked herself to all of her friends plus hundreds of other Instagram users. (Her brother, studying for an exam in the room next to hers, has spent hundreds of hours accumulating digital badges, purchased "skins." and made other investments in video games such as Fortnite and Call of Duty.)

"At this point, after investment, the trigger for the next round of behavior may become internal. The girl no longer needs a push notification to call her over to Instagram. As she is rereading a difficult passage in her textbook, the thought pops up in her mind: 'I wonder if anyone has liked the photo I posted 20 minutes ago?' An attractive off-ramp appears in consciousness (step 1). She tries to resist temptation and stick with her homework, but the mere thought of a possible reward triggers the release of a bit of dopamine, which makes her want to go to Instagram immediately. She feels a craving. She goes (step 2) and finds that nobody liked or commented on her post. She feels disappointment, but her dopamine primed brain still craves a reward, so she starts looking through her other posts, or her direct messages, or anything that shows that she matters to someone else, or anything that provides easy entertainment, which she finds (step 3). She wanders down her feed, leaving comments for her friends along the way. Sure enough a friend reciprocates by liking her last post. An hour later, she returns to her study of photosynthesis, depleted and less able to focus."

Symptoms of withdrawal

p. 135

"[Anne Tembke] says that 'the universal symptoms of withdrawal from any addictive substance are anxiety, irritablity, insomnia, and dysphoria." Dysphoria is the opposite of euphoria; it refers to a generalized feeling of discomfort or unease. This is basically what many teens say they feel-and what parents and clinicians observe- when kids who are heavy users of social media or video games are separated from their phones and game consoles involuntarily. Symptoms of sadness, anxiety, and irritability are listed as the signs of withdrawal for those diagnosed with internet gaming disorder."

Correlation with LGBTQ

p. 138

"A third reason for skepticism is that the same demographic groups that are widely said to benefit most from social media are also the most likely to have bad experiences on these platforms. The 2023 Common Sense Media survey found that LGBTQ adolescents were more likely than their non-LGBTQ peers to believe that their lives would be better without each platform they use.69 This same report found that LGBTQ girls were more than twice as likely as non-LGBTQ girls to encounter harmful content related to suicide and eating disorders. Regarding race, a 2022 Pew report found that Black teens were about twice as likely as Hispanic or white teens to say they think their race or ethnicity made them a target of online abuse.? And teens from low income households ($30,000 or less) were twice as likely as teens from higher-income families ($75,000 or higher) to report physical threats online (16% versus 8%)."

Scale matters: Group-level vs. individual-level effects

pp. 148–149

"When it was carried into schools in the early 2010s, on smartphones in students pockets, it quickly changed the culture for everyone. (Communication networks rapidly become more powerful as they grow.) Students talked to each other less between classes, at recess, and at lunch, because they began to spend much of that time checking their phones, often getting aight up in microdramas throughout the day. This meant that they made eye contact less frequently, laughed together less, and lost practice making conversation. Social media therefore harmed the social lives even of students who stayed away from it.

"These group-level effects may be much larger than the individual-level effects, and they are likely to suppress the true size of the individual-level effects."

Girls hurt other girls through relationships

p. 158

"Traditionally, boys have negotiated who is high and who is low in social status based in part on who could dominate whom if it came to a fight, or who can hurl an insult at whom without fear of violent reprisal. But because girls have stronger communion motives, the way to really hurt another girl is to hit her in her relationships. You spread gossip, turn her friends against her, and lower her value as a friend to other girls. Researchers have found that when you look at 'indirect aggression' (which includes damaging other people's relationships or reputations), girls are higher than boys—but only in late childhood and adolescence. A girl who feels her value sinking is a girl experiencing rising anxiety."

Depression spreads from women

p. 161

"In a follow-up study, Christakis and Fowler teamed up with the psychiatrist James Rosenquist to see whether negative emotional states, such as depression, also spread in networks, using the same data set. There were two interesting twists in their findings. The first was that bad was stronger than good, as is almost always the case in psychology. Depression was significantly more contagious than happiness or good mental health. The second twist was that depression spread only from women. When a woman became depressed it increased the odds of depression in her close friends (male and female) by 142%. When a man became depressed, it had no measurable effect on his friends. The authors surmise that the difference is due to the fact that women are more emotionally expressive and more effective at communicating mood states within friendship pairs. When men get together, in contrast, they are more likely to do things together rather than talk about what they are feeling."

Sociogenic epidemics

p. 161–162

"In 1997, Leslie Boss, then researcher at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, published a review of the historical and medical literature on "sociogenic" epidemics. ("Sociogenic" means "generated by social forces" as opposed to biological causation.) Boss noted that there are two variants that recur throughout history. There is an "anxiety variant" in which abdominal pain, headache, dizziness, fainting, nausea, and hyperventilation are the most common symptoms, and there is a "motor variant" in which the most common symptoms are "hysterical dancing, convulsions, laughing, and pseudoseizures." These "dancing plagues," as they are called by historians, occasionally swept through medieval European villages, leading some townspeople to dance until they died from exhaustion. For both variants, when they have occurred in recent decades, medical authorities have been unable to find any kind of toxin or environmental pollution that could have caused these symptoms. What they do find, repeatedly, is that adolescent girls are at higher risk of succumbing to these illnesses than any other groups and that the outbreaks are more likely when there has been some unusual recent stressor or threat to the community.

"Boss noted that these epidemics spread along social networks via face-to-face communication. In more recent times, she noted, they spread by reports in the mass media, such as television. Writing in 1997, in the first years of the internet, she offered this prediction: 'Development of new approaches in mass communication, most recently the Internet, increase the ability to enhance outbreaks through communication.'"

Audience capture

p. 163

"Don't just copy anyone; first find out who the most prestigious people are, then copy them. But on social media, the way to gain followers and likes is to be more extreme, so those who present with more extreme symptoms are likely to rise fastest, making them the models that everyone else locks onto for social learning. This process is sometimes known as audience capture—a process in which people get trained by their audiences to become more extreme versions of whatever it is the audience wants to see. And if one finds oneself in a network in which most others have adopted some behavior, then the other social learning process kicks in too: conformity bias."

Rise in Tourette's syndrome

pp. 163–164

"A group of German psychiatrists led by Kirsten Müller-Vahl noted a sudden increase in young people showing up at clinics claiming to have Tourette's syndrome-a motor disorder in which patients emit pronounced tics, such as heavy blinking or head and neck rotations, and in which they often emit words or sounds involuntarily. The disease is thought to be related to irregularities in a part of the brain called the basal gan-glia, which is heavily involved in physical movement. It usually emerges between the ages of 5 and 10, and 80% of those who have it are boys.

"But the German psychiatrists could see that almost none of these patients really had Tourette's. The tics were different, there had been no sign of the disease in theme when they were young, and, most revealingly, their tics were astonishingly similar. In fact, these patients—mostly young men in this first wave—were mimicking as ingle German influencer who actually had Tourette's and who demonstrated his tics in his very popular YouTube videos."

History of virtual world

p. 185

"The virtual world really began to bloom in the 1990s with the opening of the internet to the general public via web browsers such as Mosaic (1993) and AltaVista (1995), and the development of full-fledged 3-D graphics. New video game genres were developed, including "first-person shooter" games such as Doom, and later, massively multiplayer online games such as RuneScape and World of Warcraft.

"In the 2000s, everything got faster, brighter, better, cheaper, and more private. The arrival of Wi-Fi technology increased the utility and popularity of laptop computers. Broadband high-speed internet spread quickly in this decade, making it much easier to watch videos on YouTube or Pornhub and play highly engaging online multiplayer video games on the newly released Xbox 360 (2005) and P$3 (2006). These internet-connected consoles enabled adolescents to sit alone in a room, playing for extended hours with a shifting set of strangers from around the globe. Prior to this, when boys played multiplayer video games, the other players were their friends or their siblings, sitting next to them and sharing excitement, jokes, and food.

"As adolescents of both sexes got their own laptops, cell phones, and internet-connected gaming consoles, everyone was increasingly free to retreat to private spaces and do as they pleased. For boys, this opened up many new ways to satisfy their desires for agency as well as communion. In particular, it meant that boys could spend much larger amounts of time playing video games and watching pornography while alone in their bedrooms. They no longer had to use the family desktop computer or gaming console out in the living room."

The friendship recession

p. 193

"Furthermore, if video games really are a net benefit for friendships, then today's boys and young men should have more friends and be less lonely than those of 20 years ago. But in fact, the opposite is true. In 2000, 28% of 12th-grade boys reported that they often feel lonely. By 2019, that had risen to 35%. This is symptomatic of a broader 'friendship recession' among men in the United States. In the 1990s, only 3% of American men reported having no close friends. By 2021, that number had risen fivefold. to 15%."

Émile Durkheim and anomie

In 1897, the French sociologist Émile Durkheim—perhaps the most profound thinker about the nature of society—wrote a book about the social causes of suicide. Drawing on data that was just becoming avail. able as governments began to keep statistics, he noted that in Europe the general rule was that the more tightly people are bound into a commu nity that has the moral authority to restrain their desires, the less likely they are to kill themselves.

A central concept for Durkheim was anomie, or normlessness—an absence of stable and widely shared norms and rules. Durkheim was concerned that modernity, with its rapid and disorienting changes and its tendency to weaken the grip of traditional religions, fostered anomie and thus suicide. He wrote that when we feel the social order weakening or dissolving, we don't feel liberated; we feel lost and anxious:

"'If this [binding social order] dissolves, if we no longer feel it in existence and action about and above us, whatever is social in us is deprived of all objective foundation. All that remains is an artificial combination of illusory images, a phantasmagoria vanishing at the least reflection; that is, nothing which can be a goal for our action.'

"That, I believe, is what has happened to Gen Z. They are less able than any generation in history to put down roots in real-world communities populated by known individuals who will still be there a year later. Communities are the social environments in which humans, and human childhood, evolved. In contrast, children growing up after the Great Re-wiring skip through multiple networks whose nodes are a mix of known and unknown people, some using aliases and avatars, many of whom will have vanished by next year, or perhaps by tomorrow. Life in these networks is often a daily tornado of memes, fads, and ephemeral micro-dramas, played out among a rotating cast of millions of bit players.

"have no roots to anchor them or nourish them; they have no clear set of norms to constrain them and guide them on the path to adulthood.

"Durkheim and his concept of anomie can explain why all of a sud-den, in the early 2010s, boys as well as girls began to agree much more vigorously with the statement "Life often feels meaningless."

"Boys and girls have taken different paths through the Great Rewir-ing, yet somehow they have ended up in the same pit, where many are drowning in anomie and despair. It is very difficult to construct a meaningful life on one's own, drifting through multiple disembodied net-works. Like Johann Hari's godson, their consciousness ends up "broken into smaller, disconnected fragments." Human children and human bod-les need to be rooted in human communities."

The power of collective experiences

p. 203

"This is one of the founding insights of sociology: Strong communities don't just magically appear whenever people congregate and communicate. The strongest and most satisfying communities come into being when something lifts people out of the lower level so that they have powerful collective experiences. They all enter the realm of the sacred together, at the same time. When they return to the profane level, where they need to be most of the time to address the necessities of life, they have greater trust and affection for each other as a result of their time together in the sacred realm. They are also happier and have lower rates of suicide, In contrast, transient networks of disembodied users, interacting asynchronously, just can't cohere the way human communities have from time immemorial, People who live only in networks, rather than communities, are less likely to thrive."

The power of breaking bread

p. 205

"Perhaps the most important embodied activity that binds people together is eating. Most major holy days and rites of passage involve a feast, or at least a shared meal, often with foods specific for that day or ritual. Imagine how you'd feel if you were an American and someone in your family said on Thanksgiving that he was feeling hungry so he was going to take his portion of turkey, stuffing, and cranberry sauce now, an hour before dinner, and eat it alone in another room. Then he'd come back and sit with the family while they ate. No. The assembled family and friends must share the food, and this is among the most widespread of human customs: People who 'break bread' together have a bond? The simple act of eating together, especially from the same plate or serving dish, strengthens that bond and reduces the likelihood of conflict. This is one deficiency the virtual world can never overcome, no matter how good VR gets."

Intuitions first, reasoning second

p. 211

"Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second. In other words, we have an immediate gut feeling about an event, and then we make up a story after the fact to justly our rapid judgment—often a story that paints us in a good light."

How advertising-driven businesses work

p. 230

"For businesses that earn revenue based on displaying ads alongside user-generated content, there are three basic imperatives: (1) get more users, (2) get users to spend more time using the app, and (3) get users to post and engage with more content, which attracts other users to the platform."

Polynesian expression about whales and minnows

p. 247

"There is a Polynesian expression: 'Standing on a whale, fishing for minnows,' Sometimes it is better to do a big thing rather than many small things, and sometimes the big thing is unnoticed but right underfoot."